Gerald Norman was a Corporal in Battery B of the 282nd Field Artillery Battalion in World War II. He was a military scout and sharpshooter, and during WWII, fought in: Northern France, Normandy, Rhineland, Ardennes, and Central Europe. Under General Order 33 of the War Department (1945), he won the EAME (European African Middle Eastern) Campaign Medal with 5 Bronze Stars, as well as the American Defense Service Medal. And, after serving approximately 21 months in Europe and a total of 4 years, 2 months in the army altogether, he was released from service on September 6, 1945.

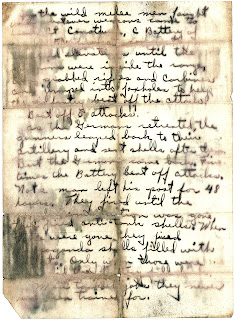

Recently, we found a handwritten memory of one of the battles he fought in. Though it was all folded up, and blurry and smudged around the edges, you can still read the majority, which has been scanned and reproduced for you here. We punched the color up in Photoshop in an attempt to make out the more illegible words; with some it helped, with others, not so much. Below the scan of the actual "story," is a typed-out version, with blank spaces for the words I couldn't quite make out. Also, there is a (?) after words I am unsure about.

We have no idea if this story was written just after this battle occurred, or later when Gerald had returned home. We don't know if there is, or was, anymore to it, as this is the only page we have found. It is very short, but you can tell the experience left quite an impression on Gerald for him to have felt it necessary to preserve the memory in writing.

|

| Gerald Norman's Memory of a WWII Battle. (Click to enlarge) |

In the wild melee men fought

with whatever weapons came to

hand. At Consthum, C Battery of

the 687 F. A. fired at ___ ___

___ elevations until the

Germans were inside the range,

then grabbed rifles and Carbines

and jumped into foxholes to help

the infantry beat off the attacks.

Beat off 5 attacks.

As the Germans retreated, the

gunners leaped back to their

artillery and sent shells after them.

But the Germans came back. Five

times the battery beat off attacks.

Not a man left his post for 48

hours. They fired until the

regular ammunition was gone,

They fired anti-tank shells. When

those were gone they fired

propaganda shells filled with

___. Only when those were

___ did the infantry/artillery(?) fall back.

Men tackled jobs they never

had been trained for.

Now, I am no expert on WWII, so I had to do a bit of research to try and figure out what Gerald's note is all about. Please, feel free to correct me if I get anything wrong, and I do suggest conducting your own research if this subject interests you. Research says Consthum was a small village (it has since been incorporated into the newly created commune, Parc Hosingen) near Luxembourg, which is the capital city of the country with the same name. It is one of the places that played an important role in the early days of the Battle of the Bulge, which was probably the biggest battle that occurred during the Ardennes Campaign of WWII. Consthum was one of several towns along the road to Luxembourg City that the Americans needed to control, in order to make it more difficult for the Germans to make it Luxembourg, which was their main objective. As the Germans advanced, there were battles in each of these villages. You can read more about the 687th Field Artillery and their contributions to this particular campaign, here.

| ||

| WWII Memorial in Consthum, Luxembourg. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Closeup of the center of the memorial. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons |

I cannot imagine experiencing anything these men experienced, much less living to tell the tale. When researching the regiment Gerald was in, I came across this passage written by Daniel Clayton, from War, Literature & the Arts, about interviews he conducted with Phil Antonelli, a veteran of the 282nd Field Artillery Battalion, the same one Gerald was in. It pretty much says it all:

Phil Antonelli enlisted in the Army shortly after graduating from high school in 1942. He served with the 282nd Field Artillery Battalion attached to Patton's Third Army and fought in every campaign in northern Europe from the Battle of Normandy to the end of the war in Germany. Phil also witnessed the atrocities at Ohdruf. All his adult life, Antonelli suffered recurring nightmares of incoming artillery in a counter-battery exchange. He'd grab his wife in the middle of the night and press her under the covers with him, crying out to "Get down. Get down!!" Phil wasn't diagnosed with PTSD until 2002, but it is likely that his case was a reactivation of the disorder that manifested itself on and off throughout his life, beginning shortly after the war ended. In talking about the German enemy, Phil told me on several occasions that he held nothing against the Germans; they were soldiers who did their duty (Clayton interviews with Phil Antonelli).